Moldova’s Productivity Trap: Why Good Firms Can’t Grow

Part of "The Next Economy: Moldova 2030" Series

Editorial Note: This article is written by Mihnea Constantinescu, Deputy Governor of the National Bank of Moldova, as part of Moldova Matter’s new series “The Next Economy: Moldova 2030.”

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the National Bank of Moldova.

Moldova’s economy faces a persistent puzzle. Entrepreneurs start businesses regularly. In a good year, agricultural exports flow steadily. Yet the country’s productivity growth lags far behind its European neighbors. The problem is not lack of ambition, it’s that firms enter small and stay small, do not innovate and only rarely are able to cover the fixed costs of internationalization. Given the small internal market size, exporting is the most likely growth source. Several concrete mechanisms trap enterprises in low-productivity equilibrium, regardless of how hard entrepreneurs work or how good their business ideas might be. Lack of credit is only one part of the answer.

The Information Problem: When Nobody Knows Who’s Creditworthy

At the heart of Moldova’s growth constraint lies a fundamental information asymmetry. Banks need to know: Is this borrower reliable? Will they repay? What assets can secure the loan if things go wrong? In developed economies, these questions get answered through comprehensive credit bureaus, transparent financial statements, and enforceable collateral registries. In Moldova, these information channels are either broken or non-existent.

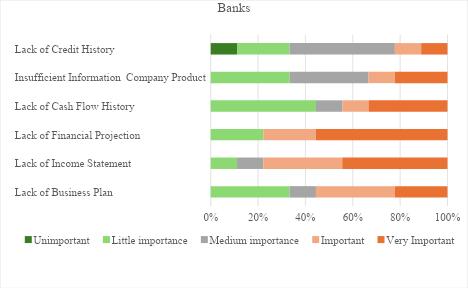

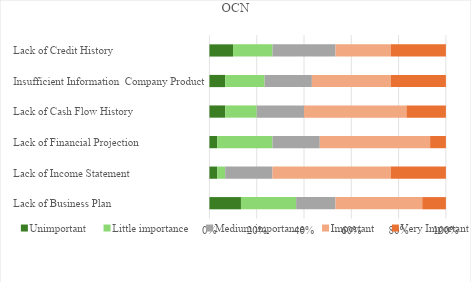

My survey of Moldova’s financial institutions (Constantinescu (2025)1) reveals how this plays out in practice. Survey participants, nine commercial banks and 54 non-bank credit organizations (OCNs), indicate they operate in essentially different markets. Not by choice, but because they are responding rationally to different information environments.

Banks concentrate on firms that can provide detailed documentation: 78% consider comprehensive financial statements critical for lending decisions, and 89% rate real estate collateral as very important. When you can’t easily verify a firm’s payment history, operational capabilities, or growth prospects, you default to what you can see and measure: buildings you can seize if the loan goes bad, and audited accounts that external professionals have verified.

OCNs occupy the space banks will not touch, functionally and geographically. Nearly half (48%) rely heavily on personal guarantees from business owners—essentially betting on the individual rather than the business. They evaluate firms through holistic assessments that incorporate “soft” information: most likely reputation in local communities, observed business practices, character judgments. This works for very small loans, but it’s expensive to scale and inherently risky.

The result? According to the World Bank Enterprise Survey, the 35-percentage-point gap between medium firms’ bank usage (50%) and small firms’ usage (15%) represents one of Eastern Europe’s widest disparities. The same survey indicates that ninety percent of small Moldovan firms rely exclusively on internal financing, growing only as fast as they can save.

The Shadow Economy Connection: Skills or Incentives?

Survey data in Figure 1 shows almost 80% of banks cite inadequate or absent Financial Projections as critical for rejection. The obvious story: firms lack financial literacy. But consider the entrepreneur’s view. Formalization brings immediate costs—taxes, compliance, fees—for uncertain benefits. When would you formalize? Only when credit access benefits clearly exceed taxation costs. Those profits come about when answering a nontrivial list of questions: Do I get higher sales in an uncertain environment? Can I access new markets? Are my production costs stable and predictable? That benefit rarely materializes in an environment with substantial exogenous shocks each year, affecting both lenders and borrowers.

Over half of banks and 40% of OCNs report that their lack of long-term funding constrains lending. Credit maturities rarely exceed 18 months because Moldova’s institutional foundations feel fragile. Property rights seem uncertain. Courts struggle with commercial disputes. Contract enforcement is slow.

Banks want formal documentation, but formalization is expensive. Firms would formalize for five-year growth capital, but credit extends barely past a year. Each actor behaves rationally given their constraints, the outcome is systematically bad for everyone. A series of flawed incentives become the driver of a two-tier credit market swirling forward the vicious circle of informality.

The Collateral Registry: Where Legal Theory Meets Market Reality

In theory, collateral registries solve a core problem: they create clear, enforceable property rights in pledged assets, expanding credit access beyond firms with real estate.

But approximately 30-45% of financial institutions report judicial enforcement as completely inefficient (more details available in Constantinescu (2025)). When recovering collateral takes months or years with unpredictable outcomes, secured lending becomes fiction. Banks stick to real estate, the one asset where seizure is somewhat predictable. Firms without real estate cannot access bank credit regardless of business fundamentals. Even successful firms remain trapped. As they grow and improve operations, they cannot properly signal improved creditworthiness because the collateral that would facilitate “graduation” to bank financing remains legally ambiguous.

The Lock-In Effect: How First Relationships Become Traps

Once a firm establishes an OCN relationship, that OCN accumulates private information about the firm’s payment behavior and operational capabilities. This relationship-specific information is not easily transferable to other lenders. The firm may then become informationally captive to that first lender. Even improvements such as increased revenues, professionalized operations, translate only modestly into better financing terms because they cannot be credibly and easily communicated to alternative lenders. The firm faces a binary choice: accept existing creditor terms or forgo external financing.

This explains Moldova’s peculiar enterprise structure: abundant small firms, very few medium-sized firms, and a handful of large firms (often foreign-owned or connected to international value chains). The missing middle is not missing because entrepreneurs lack ambition, it’s missing because the past legal and infrastructure setup led to an information architecture that prevented growth.

Beyond Finance: Why Credit Alone Won’t Fix This

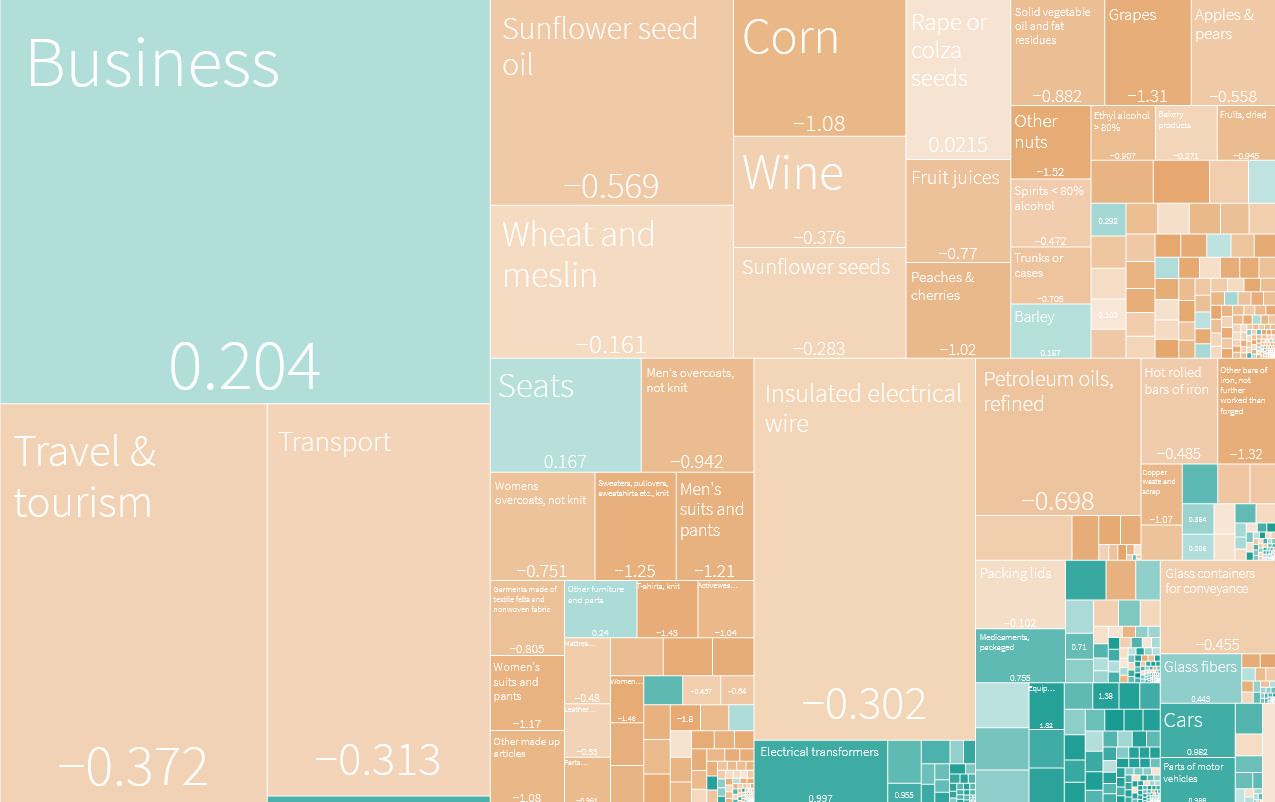

Even substantially improved credit access cannot drive productivity transformation when firms lack innovative capacity to use that capital effectively. Moldova’s export diversification record tells the story. Between 2008-2023, Moldova introduced merely 12 new export product categories, contributing just $40 per capita. Compare this to Romania’s 33 new products ($244 per capita) or Lithuania’s 26 products ($361 per capita). The perceived financing gap may signal a broader innovation and internationalization gap.

Small firms lack resources for R&D, technical expertise to identify and adopt new technologies, and organizational capabilities to implement productivity-enhancing changes needed to export. Providing these firms with more credit will not automatically solve their innovation deficit, they may simply finance continued production using outdated methods, perpetuating low productivity even as debt burdens increase.

Starting From Strength: Why Agro and Biotech Make Strategic Sense

The financial constraints described earlier reveal only half of Moldova’s growth challenge. Even with improved credit access, firms need something more fundamental: the knowledge, capabilities, and market connections that transform capital into productive growth. This is where industrial strategy2 shifts from fixing financial plumbing to building productive capacity. Moldova’s path forward leverages what exists: agricultural know-how, food processing infrastructure, and fermentation expertise from wine production. These quaint traditions, with the right tech mix can turn into industrial capabilities with direct biotech applications.

Wine production requires precise fermentation control, microbiology understanding, and quality management systems. These capabilities translate directly into producing biofertilizers, probiotics, and enzyme preparations. Agricultural waste, grape pomace, sunflower husks, corn stalks, becomes valuable feedstock for biotech processes rather than disposal problems. Processing facilities can be retrofitted incrementally rather than requiring expensive greenfield investment.

This makes technology adoption divisible rather than lumpy. A wine producer can experiment with probiotic production using existing fermentation equipment, test markets, build expertise, and scale gradually. Compare this to semiconductor manufacturing or aerospace, where minimum efficient scale requires hundreds of millions in upfront investment. Agrotech allows firms to learn by doing without existential risk.

The territorial dimension matters too. Moldova’s agricultural sectors span rural regions that urban-concentrated IT strategies would bypass. Connecting these regions through upgraded bio and agrotech creates inclusive growth rather than exacerbating rural-urban divides. A dedicated IT element should be further developed, as it provides essential complementary capabilities to developing a knowledge driven transformation of the agricultural sector.

The Cluster Model: Why Firms Need Neighbors

Individual firms struggle to build the complementary capabilities modern industries require. A biofertilizer producer needs testing laboratories, specialized cold-chain logistics, and regulatory expertise for EU standards. Building all this in-house is prohibitively expensive. Geographic concentration of related firms creates shared infrastructure no single company could build alone. Testing facilities serve multiple firms. Specialized suppliers emerge. Knowledge spills through labor mobility and informal interactions. Ideally, universities and research centers may share research facilities with new startups (Editorial note3).

Clusters also solve the coordination problem in industrial upgrading. Firms invest when confident others will make complementary investments. But clusters don’t spontaneously appear. They need anchors, large innovative companies that stabilize cost and revenue stream of SMEs interacting with it.

Anchor Firms: Accelerating Knowledge Transfer

Global value chain integration becomes essential here. An anchor firm, typically a multinational with established networks, brings what domestic SMEs cannot build independently: proven processes, quality standards, market access, and credible knowledge about what works. When an anchor establishes operations, it creates a template. Suppliers must meet its standards, forcing capability upgrading. Trained workers eventually move to other firms or start their own, disseminating knowledge. Its success signals Moldova can execute, attracting additional anchors.

The learning is concrete. Consider a beverage multinational sourcing probiotic ingredients. Its Moldova supplier must meet precise microbial counts, stability specs, and delivery reliability. Meeting these forces investments in quality control, process documentation, and supply chain management. But the multinational also provides technical assistance, shares testing protocols, conducts training audits, and offers long-term contracts justifying investment. More critically, it offers access to international markets with proven niches. This is infinitely faster and less risky than learning by trial and error in export markets. The anchor already knows which markets pay premiums, what specifications they require, and how to navigate regulations. It absorbs internationalization risk while suppliers focus on execution.

Beyond Dependence: Building Autonomous Capability

Global value chain integration is not the endpoint. Firms successfully serving anchor requirements accumulate more than revenue. They build proprietary capabilities, develop technological understanding, and establish reputations for reliability. This accumulated capability enables eventual spin-out. The supplier that mastered probiotics for a beverage multinational can develop branded products. It understands production technology, has established quality systems, knows cost structure, and has proven execution. Most importantly, it has cash flow from anchor contracts financing product development without the desperate constraints strangling SME innovation.

Chilean salmon farming exemplifies this trajectory. Firms initially supported by Japanese and US collaborators, integrated as low-tier suppliers to multinationals, gradually absorbing technology and market knowledge. Over two decades, Chilean firms progressed from basic processing to sophisticated breeding, nutrition science, and proprietary genetics. Today they compete globally. Quite likely they couldn’t have reached that position without the protected learning environment global value chain integration provided. The same holds across several success stories in different industries and geographies4.

Moldova’s trajectory could follow a similar logic. Firms master biofertilizer production serving a multinational’s regional operations, then develop specialized formulations for Moldova’s specific soil conditions, eventually exporting proprietary products to similar territories in Central and Eastern Europe. The anchor relationship provides stability and knowledge transfer making this progression possible.

The path from financial exclusion to productive capability is not direct but becomes navigable. Fix information asymmetries trapping firms in credit constraints. Build clusters providing essential shared infrastructure. Attract anchors accelerating knowledge transfer. Create space for graduation from dependence to autonomy. Each step builds on the previous, addresses real constraints, and calibrates to Moldova’s actual capabilities rather than borrowed templates.

Constantinescu, M. (2025) “Percepții și Provocări în Creditarea IMM-urilor in Republica Moldova”, Banca Nationala a Moldovei. Available at https://bnm.md/ro/content/perceptii-si-provocari-creditarea-imm-urilor-republica-moldova

Constantinescu, M. (2005) “Strategia Integrată de Dezvoltare Economică a Moldovei”. Available An economic development strategy for Moldova by Mihnea Constantinescu :: SSRN

Editorial Note: Right now Moldovan universities do not do any research. This is walled off in the Academy of Sciences and there is no relationship there either with students or the private sector. Moldova’s best high tech growth engine is being kept in a walled garden that is suspicious of business.

Iizuka, M., & Gebreeyesus, M. (2016). “Using Functions of Innovation Systems to Understand the Successful Emergence of Non-traditional Agricultural Export Industries in Developing Countries: Cases from Ethiopia and Chile” European Journal of Development Research, 29(2).