The following is a guest post from The Cathy Byrd, a creative nomad, writer, podcaster and current Peace Corps Response Volunteer in Moldova. You can follow her Substack “The Cathy Byrd Project” at this link.

In Chișinău, Moldova’s capital city, spring and summer months are for reveling outdoors—filled with joyous singing and dancing, eating and drinking. It’s impossible to keep track of all the festivals that draw crowds to the city center, nearby villages, and vineyards. Celebrations of youth, family, Romanian culture, art and craft, food and wine animate the capital’s Great National Assembly Square for days on end.

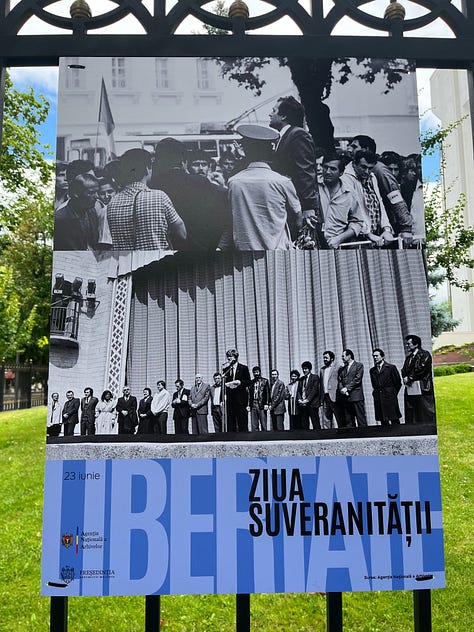

Assembly Square is a commanding platform for many civic observances, too. In a recent editorial on Agora.MD, local journalist Diana Guja reminds us that the Square is “the sacred space” where Moldovan history is made, where citizens have stood tall, demanding their right to the Romanian language, to independence, to freedom. Established on June 23, 1990, Sovereignty Day marks the adoption of the Declaration of Sovereignty, the first step toward establishing the Republic of Moldova. Since 2006, Moldova has celebrated Europe Day on May 9 to herald the country's progress towards European integration and its partnership with the European Union. These holidays regale achievements of the past and hopes for the future with flags and fanfare, speeches, musical performances, and educational displays.

Darker times in Moldovan history do not go unnoticed. Every year, in early July, the city’s sunny mood shifts when two rusted train cars appear on the Square. Their silent shadow signals a month of reflection that begins on July 6, with a day of mourning for the loss and hardships wrought by mass deportations orchestrated during the Soviet Socialist Regime (SSR) from 1940 to 1951, in the territory that is now the Republic of Moldova. In 2025, the memorial rally marked 76 years of remembrance.

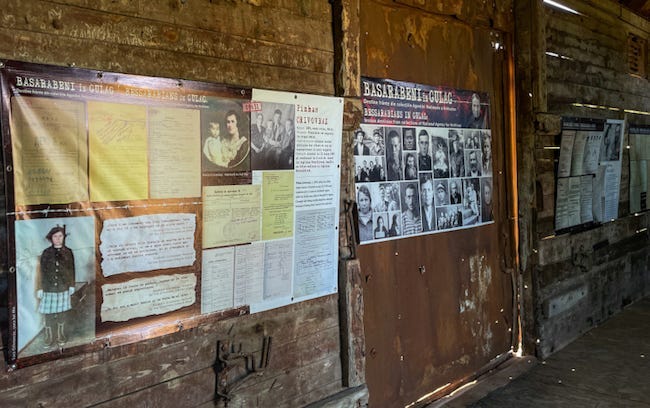

With some trepidation, I decided to school myself in what I knew would be a heart-wrenching history. I went to see for myself how the deportation story is preserved and shared. The 15-minute walk from my flat to the Square left me drenched in sweat, overwhelmed by the oppressive July heat. I stepped up into the half-light inside the train cars to study "Soviet Terror in the Moldovan SSR: Scale, Victims, and Perpetrators." The exhibition remembers when tens of thousands of Moldovans (historically known as Bessarabians) were forcibly taken to Siberia and Kazakhstan in three waves of deportations. Inaugurated in 2023, the annual display is housed in boxcars identical to those used for the exile operation. Photographs, documents, books, and other artifacts chronicle the lives of deportees and describe how their displacement was planned and carried out.

Deportation Operation

Moldovans forced to leave their homeland were condemned by the SSR for being “wealthy,” or accused of collaborating with “the fascists,” expressing radical views, belonging to “bourgeois” political parties or illegal religious sects.

Deportation was a calculated covert scheme. Beginning in the early morning hours, two or three armed soldiers and a security worker were to knock on a window or door of the properties where the accused resided. Taking each household by surprise, they gave orders with sudden brevity: “In a quarter of an hour, be ready!” Families were loaded onto trucks or carts and taken to the nearest train station. In the first deportation, families were allowed to take only few belongings with them.

In the deportation of 1941, family members were separated into three groups: heads of families, young people over 18, and women with small children and the elderly. They boarded freight cars, 70-100 people each, without water or food. The journey to their destinations took two to three weeks. In the mid-summer heat, they lacked sufficient drinking water. They were given only salted fish to eat. More than a few did not survive the trip. Deportees were given work assignments. Heads of families were taken to the forced labor camps known as “gulags.” Women, children, and the elderly were sent to Siberia or Kazakhstan to work in the forestry industry, on state farms, and in craft cooperatives.

The 1949 and 1951 deportations were referred to as “resettlements.” Families were allowed to stay together. Permitted to take personal belongings and tools, they were better equipped to build new lives far from home.

Three Waves of Loss

June 13, 1941—The first deportations began at 2:30am on June 13, 1941.

July 6-7, 1949—The second mass deportation displaced the largest number of Bessarabians. The operation began at 2am on July 6 and lasted until 8pm on July 7, 1949.

April 1, 1951—The final deportation took place between 4am and 8pm on April 1, 1951. This time, the target was a religious group, members of the illegal anti-Soviet sect of Jehovah’s Witnesses and their families.

The Train of Pain

From the Square, a 40-minute walk took me to the train station where deportations took place. In the station square stands a permanent monument created by Moldova-born artist Iurie Platon. Inaugurated on August 23, 2013, the bronze sculpture stands 3 meters high and 12 meters long on an inclined platform. The form depicts a line of dark gray figures moving uphill as one—families huddle together, men and women holding babies, small children clinging to their parents. Behind them trail the wagons that brought them to the point of departure.

One Family’s Story

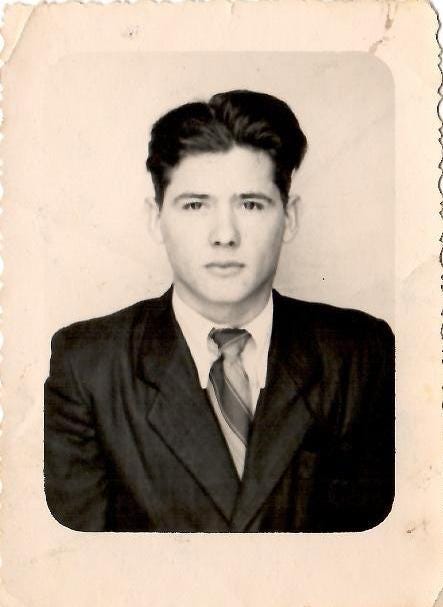

My friend Marina shared her family’s story of loss and love.

Her future grandfather, Afanasy Yakovlevich Dubalar, was 8 years old when he and his family were deported in the early morning hours of June 13, 1941. Sound asleep in their home in the village of Parkany, they heard a knock on the door and a voice commanding them to “Wake up!” In the darkness, Afanasy climbed into the back of a truck with his parents, 2 brothers, and 2 sisters. They were taken to the train station in Florești. Accused of being ‘wealthy,’ the family was allowed to bring no belongings. Their land, house, and livestock became property of the Soviet Socialist Republic. In the decade that followed, their home would serve as headquarters for SSR administrators charged with overseeing the village they left behind.

At the train station, family members were separated. Afanasy’s father stood on the platform with other men selected for transport to a gulag in Siberia. His mother hurriedly gave his father a sheepskin to comfort him on his journey. Somehow, he hid it under his shirt. What went on in the gulag where he had been sent was kept secret. Only a few whispers about ‘the man with the sheepskin’ reached his wife’s ear. She learned that her husband was devastated without his family, and that, with no clear hope for the future, he had begun refusing to eat. What became of Afanasy’s father is yet unknown.

Like most children exiled to Siberia, Afanasy and his siblings were raised by their mother. They grew up loved and cared for, despite times of extreme need, fear, hunger, and cold. In 1956, Afanasy met and fell in love with his future wife Ana. In 1957, Afanasy and Ana, along with Afanasy’s brothers and sister Lidia, returned to Moldova. Repatriated citizens, they were able to reclaim their childhood home, raise their own families, and watch their grandchildren earn advanced degrees in medicine and education. To this day, Marina’s sister continues to search for news of their missing grandfather.

Moldova’s Legacy of Creative Resistance

Last December, my Romanian language instructor told me of Moldova’s yearly mourning of the mass deportations that took place during the Soviet Socialist era. Deportations, she said, had taken away many of the country’s brightest thought leaders. The subject had come up as I was discovering ponderous evidence of legendary artists and writers on my urban walkabouts. Streets, squares, and cultural venues are named after poet laureate Mihai Eminescu. Moldova is celebrating Eminescu’s genius for the entire year in 2025. At the central cemetery, I’ve come upon mountains of flowers and candles at the gravesites of composer Eugen Doga and poet Grigore Vieru—both vocal advocates for Moldovan identity. An exhibition at the Museum of Romanian Literature introduced me to the life and work of Leonida Lari, a feminist writer in the resistance movement that led to Moldova’s sovereignty on August 31, 1991. Independence Day is the next big holiday! You can read Leonida Lari’s story HERE.

My views do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Peace Corps or the U.S. government.

To read more from The Cathy Byrd, check out her Substack newsletter here.