“The Zero Rate” Must Be Continued

Why the Exemption on Undistributed Profit Tax Should Be Made Permanent

Editorial Note: This article is written by Dumitru Alaiba, former Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economic Development and Digitalization and current member of the Supervisory Board of the National Bank of Moldova. It is part of Moldova Matter’s new series “The Next Economy: Moldova 2030.” We’ve asked experts, business leaders and economists from a variety of backgrounds to share their vision for how Moldova can develop a stronger economic future. Most articles will focus on one big idea towards this end.

In recent years, amid global instability, Moldovan companies have visibly intensified their investment activity.

This has increased firms’ capitalization. Private investments, which have been rising for six consecutive quarters, contributed positively to GDP, by +0.9% in 2024. And the state did not “lose” money from the budget; it merely postponed part of the revenues, amounting to 800 million lei.

This is not an “investment boom,” but it is a healthy direction. It is an economy learning to grow through investment, not consumption, and helping companies become stronger. Strong companies invest to produce and export more, pay more taxes, and offer higher wages to employees.

Introduction

The Moldova Growth Plan, supported by the European Union, has the ambitious objective of doubling the Republic of Moldova’s economy within the next decade. To achieve this goal, a significant part of the Reform Agenda focuses on increasing the private sector’s capacity to invest in expanding businesses, raising productivity and production capacity, improving competitiveness, and strengthening resilience to shocks.

The quality of this growth is equally important. Even an economy driven by consumption and remittances can show apparently favorable developments in key macroeconomic indicators — including GDP. However, the Republic of Moldova has committed to achieving qualitative and sustainable economic growth, where investments—not consumption—are the main driving force.

For three years, Moldova has tested a tax model for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in which corporate income is taxed only upon the distribution of dividends (referred to below as the “zero rate”).

The positive results of the first three years suggest stable growth in private investment, a positive contribution to GDP, accelerated SME capitalization, increased liquidity in the private sector, and an overall boost in productivity.

In recent years, investor sentiment has been negatively affected by multiple crises generated by external factors: the pandemic, the inflationary wave, energy shocks, two devastating droughts, the war in Ukraine, the refugee crisis, as well as unprecedented hybrid attacks from Russia against the Republic of Moldova during the recent electoral cycles. Taken together, these events created a deep sense of uncertainty, resulting in postponed investment decisions—a prudent attitude from investors, especially foreign ones.

In this difficult period dominated by overlapping crises, the “zero rate,” introduced in 2023, was one of the measures that helped Moldovan companies develop and, in fact, grow despite heightened volatility and uncertainty. But the main benefits of this reform are medium- and long-term.

Continuing the measure of taxing only distributed profit will increase the equity of Moldovan firms. Investments in machinery, equipment, technology, and wages will set off a chain of positive developments—growing production, exports, and salaries—with a positive impact on economic growth.

It is important to underline that this measure should not be seen as “lost revenues” for the public budget, but rather as a postponement of those revenues.

Because the measure expires this year (2025), it is proposed to make it permanent, extending it also to large companies, as it represents an essential instrument for supporting economic growth, investment attractiveness, entrepreneurship, and economic resilience.

Context

Introduced in 2023, the zero rate on tax for undistributed SME profits was a response to a period marked by multiple crises that hit Moldovan companies. Moreover, the response to this short-term turbulence also addressed one of the main structural blockages of Moldova’s economy—the chronic lack of capital for development and the fact that access to capital remains faulty and costly. Thus, the response to a momentary crisis also tackled a systemic problem.

Between 2023 and 2025, the Republic of Moldova applied a zero tax rate to income not distributed as dividends—i.e., the money that founders chose to keep inside the company. Withdrawal of profit as dividends, however, continued to be taxed.

A central justification for this reform was that the Republic of Moldova should not tax investments and job creation, but instead allow capital to accumulate within Moldovan companies. Taxing profit that remains in the company means taxing investment, development, and job creation. Taxing dividends, essentially, means taxing consumption.

Before the reform, companies paid 12% corporate income tax at the end of the year, and later an additional 6% on the portion distributed as dividends. Thus, there was a cumulative tax of 18% (12 + 6) on income distributed as dividends.

After the reform, the tax on undistributed profit became 0%, and only profit distributed as dividends is taxed at 18%.

Let’s take an example. A company records a profit of 1 million lei at year’s end. The founders decide to withdraw half as dividends and reinvest the other half in development.

Before the reform: The state would tax the 1 million lei profit at 12% (the company retains 880,000 lei). The 440,000 lei withdrawn as dividends would be taxed at another 6% (founders receive 413,600 lei). The company has 440,000 lei left for investment.

After the reform: The annual profit is not taxed; only the distributed half is taxed at 18% (founders receive the same 413,600 lei). The company now has 500,000 lei available for investment.

This tax model encourages profit reinvestment by applying a 0% rate to money kept inside the company—a pro-investment measure that has already shown initial results.

The “zero rate” will be an attractive offer for investors, will support economic competitiveness, and will increase Moldova’s regional attractiveness. At present, two EU member states have adopted a similar tax model—Estonia (introduced in 1999) and Latvia (introduced in 2018).

Experience from the two Baltic states suggests that this tax model has enormous long-term benefits, clearly supporting investment and helping local companies become more efficient and productive over time, while encouraging entrepreneurship and investment activity.

Both Estonia and Latvia are recognized for exemplary ecosystems that support and develop entrepreneurship, fostering vibrant startup environments and offering attractive conditions for entrepreneurs—small and large, local and foreign.

It is important to note that the 0% tax on undistributed profit—the “zero rate”—is primarily an accelerator of investment and must not be viewed as a tax cut. In the medium term, rising firm productivity will expand the tax base, mainly through increased domestic sales as production capacity grows. This means higher VAT revenues from goods and services produced in Moldova (VAT represents only about 12% of total budget revenues). At the same time, higher wage bills in more productive companies will increase the tax base for salary-related taxes—personal income tax, social insurance, and health insurance contributions—which together account for roughly 38% of total public revenues.

The Initial Objectives of the Income Tax Reform

From the outset, in 2022, the income tax reform aimed to energize the Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) sector and targeted the following main objectives:

Increasing company capital

Increasing investments — a step toward an investment-based economy

Increasing productivity by expanding production capacity

Long-term stability and predictability

Regional attractiveness and economic competitiveness

The Effects of the Reform After Three Years

A pro-investment measure

“We must shift from a consumption-based economy to an investment-based economy” — this phrase has become a cliché and was likely uttered at least once by every Minister of Economy in the last 20 years. The income tax reform under discussion is a firm step in that direction.

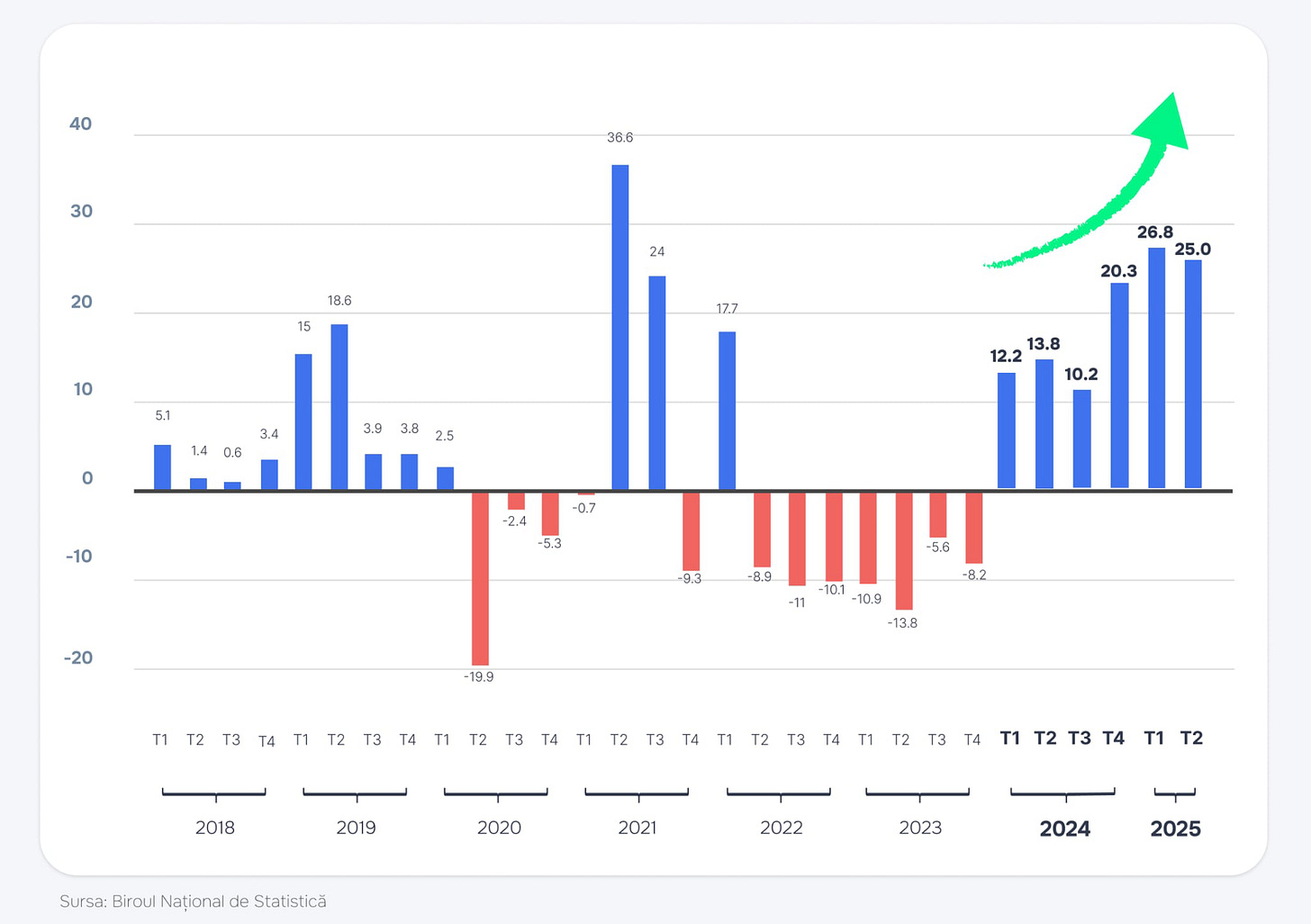

The reform has already demonstrated that it supports local companies even during crises. In a counter-cyclical development, when external factors were pulling the economy downward and uncertainty was high, Moldovan companies displayed unprecedented investment activism. Private investments have been growing for six consecutive quarters, and this dynamic will continue and accelerate if the reform that drove this behavior becomes permanent.

Since 2018, when data began being collected, private investment has never experienced such a stable period of investment activity. Even during recent years of overlapping crises, private investments contributed nearly +1% to GDP in 2024. One can only imagine what the outcome would have been in calmer times.

Note, the Q3 numbers for 2025 were just released and this trend continued with a 10.0 rate.

The additional liquidity of companies was transformed almost immediately into investments in fixed assets — machinery, equipment, vehicles, technology, software. Exactly the types of expenses that drive productivity growth. These investments increased by 12.4% in 2024 compared to 2023 (private investment only). In 2025, the trend continued, with an increase of nearly 26% in the first half of the year compared to the same period in 2024, despite an already high comparison base. This is a clear signal that the business environment invested despite volatility and uncertainty.

However, it would be a fatal mistake to conclude that we have an “investment boom.” Compared to the regional level, Moldova still suffers from a major investment deficit. We still need at least a decade to catch up, which means the measures that encourage investment must continue.

The Reform That Pulled (Fragile) Economic Growth into Positive Territory

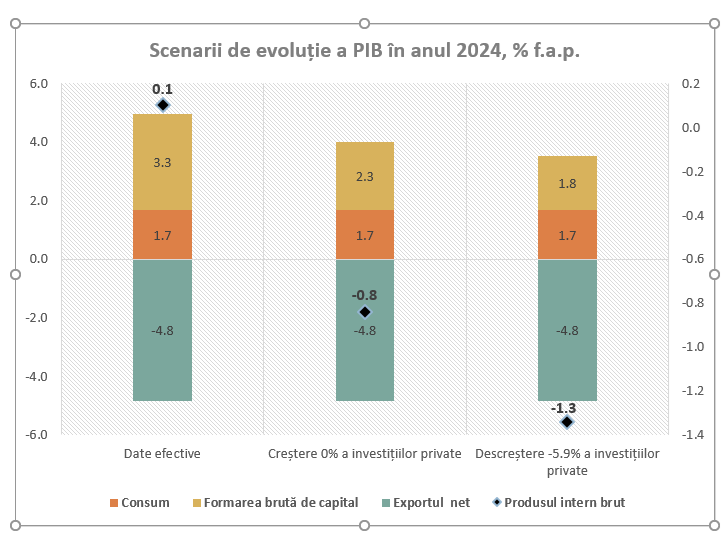

In 2024, Moldova narrowly avoided recession, and GDP recorded modest growth of +0.1% — far below what the country needs. Still, in a scenario where private investments had not grown by 12.4%, but instead stayed flat (as in the previous two years, when they had been continuously declining — see graphic above), the year 2024 would have ended with an economic contraction of –0.8%, negatively affecting economic sentiment and future growth prospects.

And if private investments had continued the 2023 trend, when they fell by 5.9%, GDP would have declined by –1.3% (assuming all other indicators remained unchanged).

If this measure were eliminated in 2026, private investment would slow down immediately. Against the backdrop of weak and slow public investment (which continued to fall in 2024 — by 9.3% compared to 2023), this component of the economy (23% of GDP) would drag GDP downward.

Overall, the effect of the three years could dissipate quickly, remaining only a temporary statistical blip rather than becoming a sustainable and long-term source of economic growth.

We would turn the private sector — which could be the engine of economic growth — into yet another brake on it.

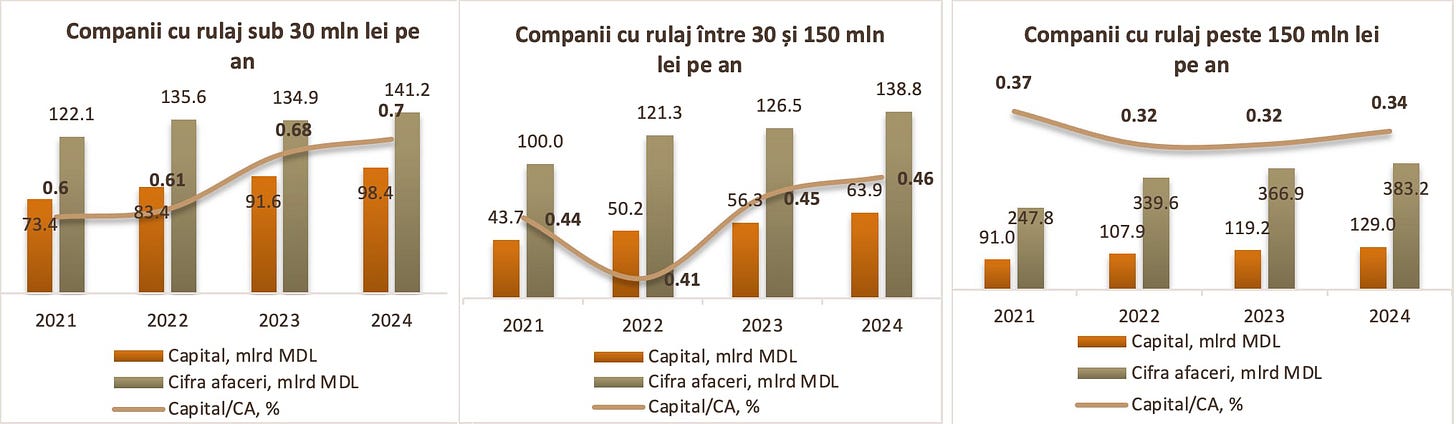

SME Capitalization

A central problem for Moldovan companies is access to capital — the trigger for positive developments in investment, productivity, and growth. Our companies do not have access to the same opportunities to finance investment projects on favorable terms, as is possible in a developed economy. For a company, capital means the ability to grow faster, greater capacity to make investments, funds available for expansion, and higher financial resilience to external shocks, along with better risk management.

Thanks to the “zero rate” available to SMEs, over the past three years — despite crises directly affecting the economy — company capitalization has grown at an impressive pace. SME capital has grown steadily for three years, primarily due to the “zero rate,” and if this measure is extended, this process will accelerate even more, like an avalanche, producing even better results in the coming years. Even so, a growth of over 20% in SME capital in just three years is remarkable.

Maintaining the 0% tax on undistributed profit will support a continued positive process of capital accumulation for Moldovan firms.

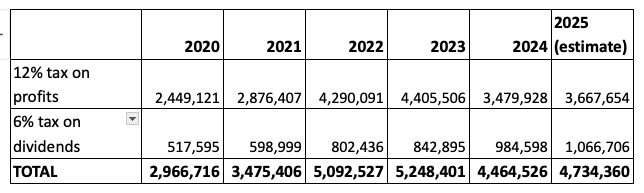

Impact on Budget Revenues

Above, we described some of the main positive effects of the income tax reform on the real economy. Let’s now look at what it “cost.”

As shown in the table above, in 2024 — the first year in which SMEs paid taxes under the new model based on 2023 financial results — they paid 925 million lei less in income tax, but 140 million lei more in dividend tax, for a total impact of roughly 800 million lei (40 million EUR).

Considering the positive impact on investment activity (+12.4%), the positive contribution to GDP, and other beneficial spillover effects, this may be the best-used 800 million lei in recent years. Especially since this is not lost revenue, but postponed revenue. The state will receive the money anyway. Within a few years, this impact will be offset by the expansion of the tax base and increased collections from other taxes and contributions.

But the big benefits lie in the future

To send a positive signal to the business community, investors, and the public — and to maintain the positive momentum in the private sector — the 0% tax on undistributed profit must be made permanent. This may be the most significant and impactful decision the new government can take to support sustainable economic growth based on investment and productivity.

Although in the first three years this measure has shown positive results at relatively low cost, its main benefits are medium- and long-term and will become visible in the years ahead.

Below are just a few of the medium- and long-term effects we should expect if this positive incentive for private-sector development is maintained.

Accelerating private-sector capitalization — the avalanche effect

Compared to the size of European companies, even the largest Moldovan company is tiny. We need a long-term effect that drives our companies to grow in scale. Moldovan firms lack capital, and this reform significantly helps address this issue.

The first three years — in which SME capitalization increased rapidly — represent only “the tip of the iceberg.” Year by year, this pace is expected to accelerate, and with this evolution, a virtuous circle will emerge, driving the development of Moldovan companies and helping Moldova achieve its main economic mission: building an investment-based economy.

Supporting investment and accelerating economic growth

The “zero rate” accelerates the development of Moldovan companies. The first three years of the reform show that entrepreneurs use the additional liquidity by directing part of the undistributed profit toward investment. Private investments contributed nearly 1% to GDP growth, and this process can continue, maintaining positive economic momentum.

Supporting domestic producers: productivity and competitiveness

The main destination of private investment in the past three years has been machinery, equipment, vehicles, and intellectual property (software). In other words, exactly what Moldovan companies need to increase productivity and competitiveness.

As investments translate into increased productivity, companies become more competitive, produce more, and sell more. Thus, in the medium and long term, this measure supports local producers of goods and services.

Export competitiveness

Moldova collects roughly two-thirds of VAT from imports and only one-third from domestically produced goods. The proposed measure removes part of the tax burden from domestic producers, helping them compete more effectively against imported products.

By making this income tax model permanent, Moldova introduces a long-term measure for gradually balancing the trade deficit. The competitiveness of Moldovan-made goods will increase, with positive effects on foreign trade dynamics.

Positive impact on the Current Account

Moldova has a long-term issue — a persistent current account deficit. Investments typically have a short-term negative effect on the current account because they require importing machinery and equipment. However, over time, these investments help reduce the deficit sustainably by activating new production capacities and, consequently, new export capacities.

Simplification and predictability

Beyond economic benefits, this measure contributes to the ongoing effort to simplify Moldova’s tax system, which is burdened with too many tax regimes, too many taxes, and too many exemptions — resulting in a system that is complex, costly, hard to understand, hard to comply with, and hard to administer.

If this measure becomes permanent, Moldovan companies will gain the level of predictability needed to plan and carry out multi-year investments, knowing that by retaining profit, they will have 12% more liquidity at year-end. This further accelerates investment activity.

Private sector resilience in crises

The resilience of an economy starts with the ability of a critical mass of companies to withstand shocks. The “zero rate” has also shown that entrepreneurs use liquidity prudently, building reserves and managing uncertainty more efficiently. While it is hard to quantify exactly how much “zero rate” helped companies weather the shocks of recent years, its positive contribution is easy to acknowledge.

Regional attractiveness

In recent years, the “zero rate” has been one of Moldova’s key messages to investors. Only two EU states have such a model — Estonia and Latvia. Moldova could become more competitive as the only country in the region offering this incentive. This would increase the country’s investment attractiveness, supporting foreign investment through an efficient and appealing tax policy. Combined with a very attractive tax rate of just 18% (compared to 22% in Estonia and 25% in Latvia), Moldova’s offer becomes compelling.

Sustainable economic growth

Shifting “from a consumption-based economy to an investment-based economy” means encouraging investment, and tax policy is one of the most effective tools. Moldovan companies have shown in the last three years that they have a strong appetite for investment. We can start by not taxing those investments.

Investments made by Moldovan companies will stimulate economic growth through multiple macroeconomic channels:

By increasing aggregate demand via higher gross fixed capital formation and activity in related sectors

By increasing productivity through technological modernization and innovation adoption

By increasing household income through job creation and higher wages, boosting domestic consumption

By improving external competitiveness, boosting exports, and reducing import dependency — mitigating the negative trade balance, which currently drags down economic growth

Conclusion

The Republic of Moldova is advancing rapidly toward the European Union, and the country’s existential interest is to become a full EU member as soon as possible. The EU-supported Moldova Growth Plan is an enormous opportunity for our economy. The Reform Agenda is one of the most ambitious roadmaps for improving national competitiveness, and the resources available must be used to build an investment-based economy.

A competitive, dynamic economy capable of playing an active role in the EU single market requires accelerating the development of Moldovan companies. As the results outlined above show, the “zero rate” is one of the strongest tools for achieving this objective.

This article was originally published by the European Initiative in Romanian.

I would point out that a significant portion of the reinvested profits go to the government _anyway_ as either VAT or salary taxes. So, it was just an additional tax on top of the 20-30% minimum taxes that the government receives as part of any investment. (Obviously, simplified numbers, I'm not an accountant or economist.)

The government will receive 8% of the reinvested 500k lei, as VAT as an absolute minimum, but likely it will be quite a bit more anywhere from 20-30%.

If you take that money and reinvest in just equipment or people, the government will receive VAT or salary taxes. BUT, if you are building something, the government will get 20% VAT on the brick, plus 30% to lay the brick, so depending on how exactly the costs line up, it could be up to 40% taxes on investments not including other costs for approvals, banking, accounting, stamps, etc. (Theoretically, nowadays, more VAT is refundable but even still, for large capital investments with low-sales, it functions as a no-interest multi-year loan to the government in a currency with high inflation.)

Taxes in Moldova expects that there is a grey economy, so there are a lot of taxes on top of taxes. A flat corporate tax on reinvested profit only makes sense when those corporations are were not paying salary taxes or are using schemes to avoid paying VAT.

As the economy becomes more white, then these duplicate taxes need to be consistently reduced across the board or with particular taxes, like reinvested profit, to be removed. Too much of a share of investment (especially small foreign investments) ends up in the bank's and government's hands before it even can be used by a business.